We live in an age fraught with concerns about security in the wider world, a symptom of which is the ongoing demand for more secure passports enhanced by ever smarter applications of technology – biometric data (eg, photographs, fingerprints and iris patterns), ePassports (embedded microprocessor chips), etc. The international passport today is a much valued and for some a lucrative commodity𝔸, but when did people first start to use passports as we understand the concept?

Passports or their document antecedents were known to exist in ancient civilisations – artwork from the Old Kingdom (ca.1,600 BC) depict Egyptian magistrates issuing identity tablets to guest workers; in the (Hebrew) Bible Judaean governor Nehemiah furnishes a subject permission to travel to the Persian Empire; Ancient Chinese bureaucrats in the Han Dynasty (fl. after 206BC) issued a form of passport (zhuan) for internal travel within the empire, necessary to move through the various counties and points of control.

Passports or their document antecedents were known to exist in ancient civilisations – artwork from the Old Kingdom (ca.1,600 BC) depict Egyptian magistrates issuing identity tablets to guest workers; in the (Hebrew) Bible Judaean governor Nehemiah furnishes a subject permission to travel to the Persian Empire; Ancient Chinese bureaucrats in the Han Dynasty (fl. after 206BC) issued a form of passport (zhuan) for internal travel within the empire, necessary to move through the various counties and points of control.

࿏࿏࿏

In medieval Europe the prototype travel document emerged from a sort of gentleman’s agreement between rulers to facilitate peaceful cross-border exchanges (‘The Contentious History of the Passport’, Guilia Pines, National Geographic, 16-May-2017, www.api.nationalgeographic.com)…it provided sauf conduit, allowing an enemy safe and unobstructed ”passage in and out of a kingdom for the purpose of his negotiations”. This convention however was ad hoc, haphazard and capricious, the grantor’s ‘authority’ bestowed on the traveller might not be recognised at any point in his or her travels (Martin Lloyd, The Passport: The History of Man’s Most Travelled Document (2005)). The Middle Ages nonetheless did bring advances in the formulation of travel documents for extra-jurisdiction movements. Individual cities in Europe often had reciprocal arrangements where someone granted a passport-type paper in their home city could enter a city in another sovereignty for business without being required to pay its local fees (‘When were passports as we know them today first introduced?’, (Rupert Matthews), History Extra, 29-Sep-2021, www.historyextra.com). King Henry V, he of lasting Agincourt fame, authorised just such a early form of passport/visa as proof of identity for English travellers venturing to foreign lands, leading some to credit him with the introduction of the first true passport. The issuing of travelling papers sanctioned by the English Crown were enacted by parliament in the landmark Safe Conducts Act of 1414.

A ‘passport’ letter furnished by King Charles I to a overseas-bound private citizen of the crown, dating from 1636

A ‘passport’ letter furnished by King Charles I to a overseas-bound private citizen of the crown, dating from 1636࿏࿏࿏

Before the rise of the nation-state system in 19th century Europe, large swathes of the populations of the multitudinous political entities—largely comprising serfs, slaves and indentured servants—routinely required “privately created passes or papers to legitimise their movement” (‘Papers, Please: The Invention of the Passport’, (Eric Schewe), JSTOR Daily, 17-Mar-2017, www.daily.jstor.org). Kings, lords and landowners all issued ad hoc laissez-passer of their own definition and design (Baudoin, Patsy. The American Archivist 68, no. 2 (2005): 343–46. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40294299). A systemic, standardised passport would not materialise until the 20th century.

It was only with the arrival of world war in 1914 that governments, motivated by security needs, turned their attention to tightening up entry requirements between the new nation-states, putting immigration quotas on the agenda (US legislators for example were eager to check the flow of immigrants into the country). Spearheaded by the newly created League of Nations (and aided by the availability of cheaper photography) a passport system began to evolve that was recognisably modern. The League in 1920 introduced a passport nicknamed “Old Blue”—specifying the size, layout and design of passports for 42 of its nations—thus establishing the first worldwide passport standards𝔹. Passports “became both standardized, mandatory travel documents and ritual tools reinforcing national identity” (Schewe).

It was only with the arrival of world war in 1914 that governments, motivated by security needs, turned their attention to tightening up entry requirements between the new nation-states, putting immigration quotas on the agenda (US legislators for example were eager to check the flow of immigrants into the country). Spearheaded by the newly created League of Nations (and aided by the availability of cheaper photography) a passport system began to evolve that was recognisably modern. The League in 1920 introduced a passport nicknamed “Old Blue”—specifying the size, layout and design of passports for 42 of its nations—thus establishing the first worldwide passport standards𝔹. Passports “became both standardized, mandatory travel documents and ritual tools reinforcing national identity” (Schewe).

Later the “Old Blue” passport was expanded into a 32-page booklet which included basic data about the holder such as facial characteristics, occupation and address. “Old Blue” had remarkable longevity, remaining the norm for passports until 1988 when it was superseded by a new, burgundy-coloured passport as the international standard (‘The World’s First Official Passport’, Passport Health, www.passporthealthusa.com).

(Source: WSJ Graphics)

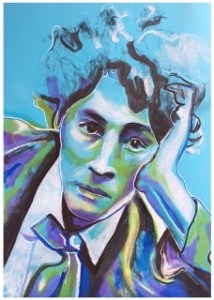

(Source: WSJ Graphics) Marc Chagall (self-portrait): one of a number of famous Nansen passport holders

Marc Chagall (self-portrait): one of a number of famous Nansen passport holders

࿏࿏࿏

End-note: Married women travellers and the ‘stateless’

As the standardised international passport took shape, married women (unlike single women) were not admitted initially into the ranks of passport-holders in their own right, rather they were considered merely “as an anonymous add-on to their husbands’ official document”, eg, ”John Z and wife” (the wife’s public identity at the time still tied very much to that of their spouse‘s). In 1917 newly married American writer Ruth Hale’s request for a passport in her maiden name to cover the war in France was denied (‘The 1920s Women Who Fought For the Right to Travel Under Their Own Names’, (Sandra Knisely), Atlas Obscura, 27-Mar-2017, www.atlasobscura.com). Also bereft of passports in the modern-state system were those refugees who found themselves stateless in the turbulent aftermath of WWI. To address this crisis the League of Nations issued ”Nansen passports”ℂ from 1922 to 1938 to approximately 450,000 refugees. Originally intended for White Russians and Armenians (and later for Jews feeing persecution under the Nazis), the “Stateless passports” allowed their holders “to cross borders to find work, and protected them from deportation (‘The Little-Known Passport That Protected 450,000 Refugees’, (Cara Giaimo), Atlas Obscura, 07-Feb-2017, www.atlasobsura.com)𝔻.

↜↝↜↝↜↝↜↝↜↝↜↝↜↝↜↝↜↝↜↝↜↝↜↝↜↝↜↝↜↝↜↝

𝔸 like the small island-states Malta and Cyprus who happily sell their citizenship to anyone who can afford it (up to US$1,000,000)

𝔹 “Old Blue” was originally written in French, just like the origin of the word ‘passport’ itself — passeport, from passer (“to pass” or “to go”) and port, meaning ‘gate’ or ‘port’

ℂ named after their promoter, Norwegian polar explorer Fridtjof Nansen

𝔻 the Stateless passports didn’t of course stop the numbers of stateless refugees from continuing to escalate alarmingly…the UNHCR estimates that the global number of stateless persons is now more than 10,000,000